Quantum Mechanics Note

Date: 2024/05/27Last Updated: 2024-05-28T12:49:25.000Z

Categories: Physics

Tags: Physics, Quantum Mechanics

Read Time: 12 minutes

0.1 Contents

- 0.2 Probability Basics

- 0.3 Calculus Basics

- 0.4 Wave Function

- 0.5 Schrödinger Equation

- 0.6 Double Slit Experiment

- 0.7 Parity of TISE Solutions

- 0.8 States of TISE Solutions

- 0.9 Continuity Equation and Probability Current

- 0.10 Quantum Tunnelling

- 0.11 Functional Analysis of Quantum Mechanics

- 0.12 Measurement Postulate

- 0.13 Measurement of Observables

- 0.14 Commutators and Lie Bracket

- 0.15 Compatibility of Observables

- 0.16 Robertson Inequality

- 0.17 Quantum Harmonic Oscillator

- 0.18 Constant of Motion and Commutators

0.2 Probability Basics

0.2.1 Random Variable

A random variable is a function that maps the sample space

to the real number line

.

0.2.2 Probability Density Function

The probability density function of a random variable

is a function that describes the likelihood of the random variable to take on a specific value.

0.2.3 Cumulative Distribution Function

The cumulative distribution function of a random variable

is a function that describes the probability that the random variable takes on a value less than or equal to

.

0.2.4 Expectation

The expectation of a random variable is the average value of the random variable.

0.2.5 Variance

The variance of a random variable is a measure of how much the values of the random variable vary.

0.2.6 Standard Deviation

The standard deviation of a random variable is the square root of the variance.

0.2.7 Probability Amplitude

The probability amplitude of a random variable

is a complex value function that the likelihood of the random variable to take on value

is given by

.

In other words, the probability density function is given by

0.3 Calculus Basics

0.3.1 Gaussian Integral

The Gaussian integral is given by

0.3.1.1 Odd Powers of %22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3Cdefs%3E%3Csymbol%20id%3D%22a%22%20overflow%3D%22visible%22%3E%3Cpath%20d%3D%22M7.905%205.595c0%20.69-.675%201.035-1.425%201.035-.645%200-1.155-.345-1.545-1.035-.315.69-.84%201.035-1.605%201.035-.735%200-1.335-.345-1.815-1.02C1.11%205.025.9%204.59.9%204.305c0-.135.075-.21.225-.21.135%200%20.225.075.255.21.285.87.915%201.89%201.92%201.89.495%200%20.735-.315.735-.93%200-.315-.27-1.485-.795-3.495C2.985.765%202.535.27%201.89.27c-.21%200-.405.045-.57.12q.585.225.585.81c0%20.39-.195.585-.6.585-.495%200-.87-.42-.87-.915%200-.69.705-1.035%201.44-1.035.63%200%201.14.345%201.545%201.035.285-.69.825-1.035%201.605-1.035.72%200%201.32.345%201.8%201.02.405.585.615%201.02.615%201.305%200%20.135-.075.21-.225.21-.135%200-.21-.075-.255-.21C6.705%201.305%206.03.27%205.055.27c-.495%200-.75.3-.75.915%200%20.195.075.615.24%201.29l.51%202.025c.285%201.125.75%201.695%201.41%201.695.21%200%20.405-.045.57-.12-.405-.135-.6-.405-.6-.81%200-.39.21-.585.615-.585.48%200%20.855.435.855.915%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fsymbol%3E%3C%2Fdefs%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E) in Gaussian Integral

in Gaussian Integral

The Gaussian integral with odd powers of is given by

As this is an odd function, the integral is zero.

0.3.1.2 Even Powers of %22%2F%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3C%2Fg%3E%3Cdefs%3E%3Csymbol%20id%3D%22a%22%20overflow%3D%22visible%22%3E%3Cpath%20d%3D%22M7.905%205.595c0%20.69-.675%201.035-1.425%201.035-.645%200-1.155-.345-1.545-1.035-.315.69-.84%201.035-1.605%201.035-.735%200-1.335-.345-1.815-1.02C1.11%205.025.9%204.59.9%204.305c0-.135.075-.21.225-.21.135%200%20.225.075.255.21.285.87.915%201.89%201.92%201.89.495%200%20.735-.315.735-.93%200-.315-.27-1.485-.795-3.495C2.985.765%202.535.27%201.89.27c-.21%200-.405.045-.57.12q.585.225.585.81c0%20.39-.195.585-.6.585-.495%200-.87-.42-.87-.915%200-.69.705-1.035%201.44-1.035.63%200%201.14.345%201.545%201.035.285-.69.825-1.035%201.605-1.035.72%200%201.32.345%201.8%201.02.405.585.615%201.02.615%201.305%200%20.135-.075.21-.225.21-.135%200-.21-.075-.255-.21C6.705%201.305%206.03.27%205.055.27c-.495%200-.75.3-.75.915%200%20.195.075.615.24%201.29l.51%202.025c.285%201.125.75%201.695%201.41%201.695.21%200%20.405-.045.57-.12-.405-.135-.6-.405-.6-.81%200-.39.21-.585.615-.585.48%200%20.855.435.855.915%22%2F%3E%3C%2Fsymbol%3E%3C%2Fdefs%3E%3C%2Fsvg%3E) in Gaussian Integral

in Gaussian Integral

The even powers of in Gaussian integral can be calculated using Feynman's trick.

0.4 Wave Function

We can postulate that the state of a particle is described by a complex value wave function , where

is the position and

is the time.

0.4.1 Born Rule

The probability density to find the particle at position is given by

.

And thus, the probability to find the particle in an measurable area

is given by

0.4.2 Continuity Requirement of Wave Function

The wave function must be continuous and differentiable.

0.4.3 Normalizing Wave Function

The wave function defined on space

is normalized if

If the wave function is not normalized, and if

is finite and greater than

, then the normalized wave function is given by

0.4.4 Superposition Principle of Wave Functions

If and

are two wave functions, then the superposition of the wave functions is given by

where and

are complex numbers.

And

is also a wave function.

0.4.5 Interference of Wave Functions

The interference of wave functions is a phenomenon where two wave functions and

interfere with each other to form a new wave function

.

Let .

Then the probability density of the new wave function is given by

And the

is usually called the interference term.

0.4.6 Classical Plane Wave

The classical plane wave is given by

where is the amplitude,

is the wave number, and

is the angular frequency.

Note: The classical plane wave is not normalizable, as the integral of the probability density is infinite. In this case, we can use

where

is a relatively small positive constant. The new wave function is normalizable and have similar behaviour to the plane wave near the origin.

0.5 Schrödinger Equation

0.5.1 Reduced Planck Constant

The reduced Planck constant is given by

where is the Planck constant.

0.5.2 Quantization Rule

The quantization rule is given by

0.5.3 Schrödinger Equation for Free Particle

In classical mechanics, the energy of a free particle is given by

By applying the quantization rule, the Schrödinger equation (SE) for a free particle with wave equation is given by

0.5.4 Hamiltonian Operator

The Hamiltonian operator is given by

Using the Hamiltonian operator, the Schrödinger equation for a free particle is given by

0.5.5 Using Separation of Variables to Solve Schrödinger Equation

The Schrödinger equation can be solved using separation of variables.

Let .

Then the Schrödinger equation becomes

Assume, solve

with

.

Then the general solution is given by

0.5.6 Time-Independent Schrödinger Equation

By the previous discussion, the task of solving the Schrödinger equation is reduced to solving the equation

This equation is called the time-independent Schrödinger equation (TISE).

We always call eigenvalues of

. And it is also known as:

- Energy lLevels

- Eigenenergies

- Energy Eigenvalues

And are called energy eigenstates of

. And it is also known as:

- Stationary States

- Energy Eigenfunctions

0.5.6.1 Degeneracy of TISE Solutions

If two or more energy eigenstates have the same energy eigenvalue, then the energy eigenvalue is said to be degenerate.

If two eigenstates have the same eigenvalue, we call it degeneracy of order 2 or twice degenerate.

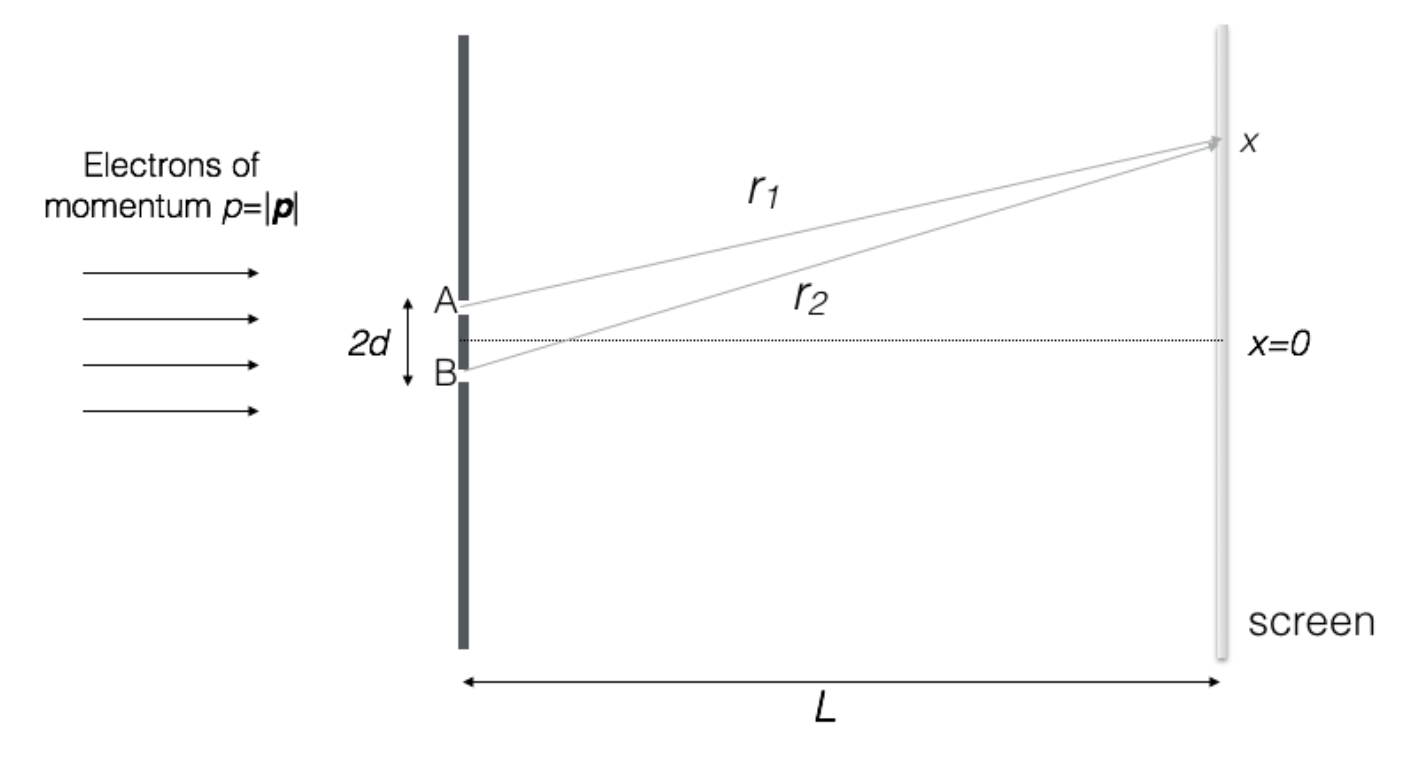

0.6 Double Slit Experiment

Consider the following double slit experiment setup.

We can assume the wave function that go through the slits and

are the same,

and is given by the analogue of plane wave

.

Then, for any point on the screen, the wave function is the superposition of the wave functions from the slits

and

.

where and

are the distances from the slits

and

to the point

.

And is given by

Without normalization, the probability density of the wave function is proportional to

We can see that the probability density of the wave function is proportional to a transformed cosine function, which explains the interference pattern on the screen.

0.7 Parity of TISE Solutions

0.7.1 Even potential and Parity

Given a potential , the potential is said to be even if

In such cases, we can assume the TISE solution has definite parity, that is:

0.7.2 Real Potential and Parity

Given a real potential , we can assume the TISE solution to have definite parity regarding conjugation, that is:

0.8 States of TISE Solutions

In general there are three kinds of states of TISE solutions:

- Bound States

- Scattering States

- Non-physical States

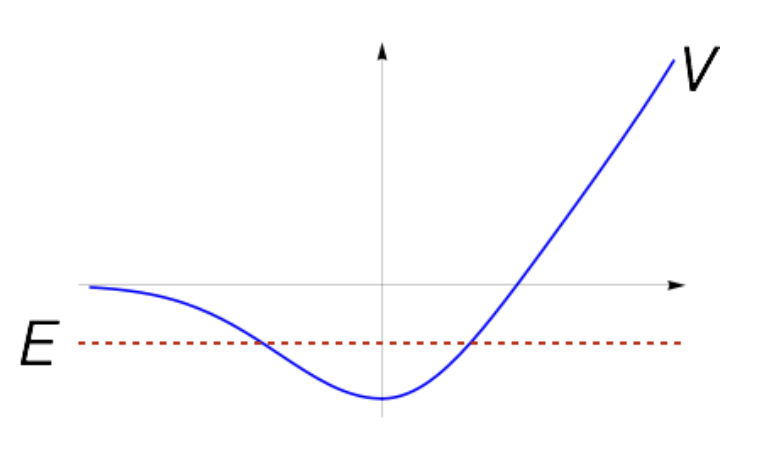

0.8.1 Bound States

Bound states are states where the energy eigenvalue is less than the potential energy at infinity and greater than the minimum potential energy.

In such cases, the TISE solution is normalizable, and the energy eigenvalue is quantized.

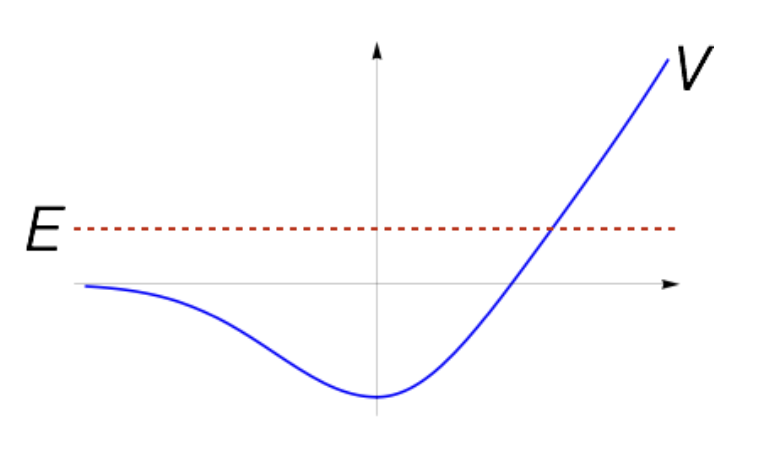

0.8.2 Scattering States

Scattering states are states where the energy eigenvalue is greater than the potential energy at infinity.

In such cases, the TISE solution is not normalizable, and the energy eigenvalue is continuous.

Scattering states can be approximated by normalizable states by similar method as the classical plane wave.

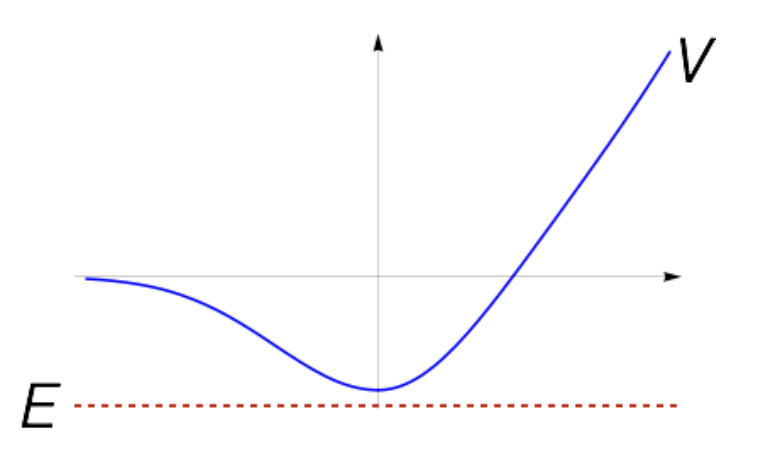

0.8.3 Non-physical States

Non-physical states are states where the energy eigenvalue is less than the minimum potential energy.

This case cannot happen in real physical systems.

0.9 Continuity Equation and Probability Current

Consider the potential to be real. Define the probability density of a wave function as

.

Then:

We thus define the probability current as

The above equation become:

and is called the continuity equation.

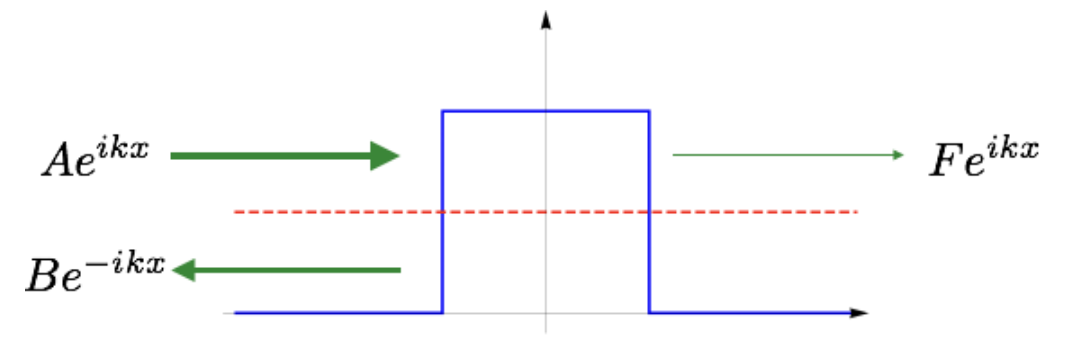

0.10 Quantum Tunnelling

We consider a potential barrier of height and width

.

That is, the potential is given by

Then, the TISE can be divided into three regions:

- Region I:

- Region II:

- Region III:

0.10.1 Simplified Model of Quantum Tunnelling

For the sake of simplicity,

let

we can assume the solution of the TISE in Region I and Region III to be

In region I:

In region III:

The wave can be interpreted as the wave go toward the barrier, and the wave

can be interpreted as the wave being reflected by the barrier and wave

can be interpreted as the wave go through the barrier.

As there is no probability for the particle to be in region II, the probability current must be same at the point and

.

In region I:

In region III:

Thus, we have

We define the reflection probability and transmission probability

as

Then, we have

0.10.2 Quantum Tunnelling through High and Thin Barrier

We consider a barrier that is infinitely high and thin at origin.

To state this formally, we consider the potential to be the limiting behaviour of the Dirac delta function potential.

and

Also, for all function , we have

Then, the potential is given by

We again, consider the simplified model in the previous section.

In region I:

In region III:

As the region II is infinity thin, the right hand side of the region I and the left hand side of the region III must be the same.

Thus, we have

Also, by integrating the TISE over the region ,

we get:

Taking the limit , we get

Substituting the solution of the TISE in region I and region III, we get

Solving the above equation, we can get the reflection and transmission probability.

0.11 Functional Analysis of Quantum Mechanics

0.11.1 Hilbert Space

Define the Hilbert space as the space of all possible wave functions

that are square integrable.

The Hilbert space is a complex vector space.

0.11.2 Inner Product

We define the inner product of two wave functions and

as

0.11.2.1 Properties of Inner Product

- Linearity in Second Argument: For all

and

, we have

.

- Anti-linearity in First Argument: For all

and

, we have

.

- Positive Definite: For all

, we have

and

if and only if

.

- Conjugate Symmetric (Skew Symmetric): For all

, we have

.

0.11.3 Norm

The norm of a wave function is defined as

0.11.4 Orthogonality

Two wave functions and

are said to be orthogonal if

0.11.5 Angle

The angle between two wave functions and

is defined as

0.11.6 Orthonormal Basis

A set of wave functions is said to be an orthonormal basis if

- The set is orthogonal.

- The set is normalized.

- The set spans the Hilbert space. That is, for all

, there exists a set of complex numbers

such that

0.11.7 Operator

An operator is a function that maps a wave function to another wave function.

0.11.8 Hermitian Conjugate

The Hermitian conjugate of an operator is denoted by

and is the unique operator that satisfies

0.11.9 Hermitian Operator

An Hermitian operator is an operator that satisfies

for all .

An equivalent definition is that the operator is equal to its Hermitian conjugate.

0.11.10 Spectral Theorem

The spectral theorem states that for all Hermitian operators , there exists an orthonormal basis

such that

where are the eigenvalues of

and is real.

0.11.10.1 Hamiltonian Operator is Hermitian

The Hamiltonian operator is Hermitian.

Proof:

0.11.11 Positivity Operators

An operator is said to be positive definite if

give any non-zero wave function

, we have

An operator is said to be positive semi-definite if

give any wave function

, we have

Any operator given by is positive semi-definite.

0.12 Measurement Postulate

Given a orthonormal basis , the measurement postulate states that the probability of measuring the normalized wave function

to be in the state

is given by

0.12.1 Post Measurement State

After the measurement, the state of the wave function will collapse to the state that is measured.

0.13 Measurement of Observables

Given an observable ,

it is postulated that

is Hermitian and has an orthonormal basis

.

The expectation value of the observable of a wave function

is given by

0.14 Commutators and Lie Bracket

In general, two operators and

do not commute.

We define the commutator (Lie Bracket) of two operators and

as

0.14.1 Properties of Commutators

- Linearity:

- Anti-linearity:

- Linearity in Second Argument:

- Distributivity:

0.14.1.1 Commutator of Position and Momentum Operators

The commutator of position operator and momentum operator

is given by

0.15 Compatibility of Observables

Two observables and

are said to be compatible if they commute.

0.16 Robertson Inequality

The Robertson Inequality states that for any two observables and

, we have

Proof:

Without loss of generality, we can assume and

. Otherwise we replace

with

and

with

.

Then, we have

By similar argument, we have

Thus,

0.16.1 Robertson Inequality for Position and Momentum Operators

Given the position operator and momentum operator

, we have

0.17 Quantum Harmonic Oscillator

A quantum harmonic oscillator is a system where the potential energy is given by

0.17.1 Annihilation and Creation Operators

Given the Hamiltonian operator of the quantum harmonic oscillator, we can define the annihilation operator

and creation operator

as

Thus, we have

If we take:

Then, we have

0.17.2 Bosonic Commutation Relation

Given the annihilation operator and creation operator

of the quantum harmonic oscillator, we have

0.17.3 Number Operator

Given the annihilation operator and creation operator

of the quantum harmonic oscillator, we can define the number operator

as

Thus, we have

0.17.4 Eigenstates of Number Operator

As the number operator is Hermitian, we can find an orthonormal basis

such that

We next prove that can only be non-negative integers.

Given an eigenvector of

with eigenvalue

, we have

Thus, if is non-zero, then

is also an eigenvector of

with eigenvalue

.

We next prove that if and only if

.

If , then

Thus, .

If , then

Thus, .

By proceeding the previous argument, we conclude that is an eigenvector of

with eigenvalue

.

If is not an integer, then

can be any positive integer as the annihilation process can be repeated indefinitely when

never hit zero.

And there exits

such that

, which is not possible,

as

, and is positive semi-definite.

Thus, is a non-negative integer.

0.17.5 Ground State of Quantum Harmonic Oscillator

By discussion in the previous section,

we can find an normalised eigenstate of the number operator

with eigenvalue

.

In this section, we prove that it is unique, up to a complex constant.

By previous discussion, we see that .

As the above equation is a first oder homogeneous ODE, and the solution is unique up to a complex constant.

0.17.6 Creation Operator and Eigenstates of Number Operator

Given the ground state of the quantum harmonic oscillator, and eigenstate

of the number operator

with eigenvalue

.

Then:

and

Thus, we could define the recursive relation:

Repeating the formula, we can get all the eigenstates of the number operator .

And could be defined by the ground state

.

0.17.7 Statistics of Quantum Harmonic Oscillator

As the creation operator and annihilation operator

are linear combinations of position operator

and momentum operator

,

we can derive the position operator

and momentum operator

in terms of

and

.

Thus, we have

and

0.18 Constant of Motion and Commutators

Given an operator ,

which is probably time dependent,

then